Back

BackThe New Spectrum of Mental Health Care

A new emphasis on culturally competent mental health care could be a game-changer for racialized women. Meet some of the leaders who are transforming mental health services and helping others connect to therapists who understand their worldviews.

When Ruby Latif was a graduate student, she led a dialogue with Canadian Muslim women about their mental health. She wanted to get a better sense of what motivates or discourages them from seeking support for their mental health.

What she discovered could help address the stark mental health disparities in the Muslim community and help other racialized women get the care they need.

Latif had good reason to be concerned. Statistics show that aggression and hate crimes motivated by Islamophobia are rising in Canada and the United States. Muslim women who wear a hijab or other religious symbols are a ready target. In fact, they face a triple jeopardy: discrimination not only due to their religion, but also their gender and race.

42%of Muslim women say they have experienced some form of discrimination or ill treatment in the past five years.

The women who shared their first-hand experiences with Latif said they felt judged. They told her that most mental health service providers didn't understand their culture and faith. And, they talked about their desire for help from people who are sensitive to their life experiences and culture.

"Even the most understanding therapists, they would always have some kind of picture of what my culture is. And it's not that. You don't understand who I am. You don't understand where I come from," according to one woman who participated.

Another said, "When I go to therapy, I leave my Muslimness at the door, because you’re never going to understand or be able to support me as a Muslim woman."

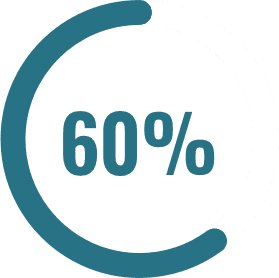

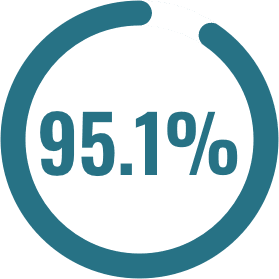

of Black Canadians said they would be more willing to use mental health services if the mental health professional were Black.

felt that the underutilization of mental health services by Black Canadian residents was an issue that needed to be addressed.

A more recent study by the Canadian Council of Muslim Women backed up these experiences. A diverse group of Canadian Muslim women cited the need for culturally relevant social and health services. Many reported spending significant time and effort educating mental health care providers who don't understand or relate to their experiences. Others said they were dismissed, denied services, or faced protracted delays in access to care and information.

Queer, disabled, and Black Muslim women, as well as newcomers and single mothers, faced the biggest barriers of all.

“I wouldn’t even know where to start looking for queer Muslim therapists — is that even a thing? … It’s so niche. I would prefer a woman of color, but beggars can’t be choosers,” said one woman.

These experiences illuminate the need for culturally competent mental health care, including mental health professionals who value and understand cultural, racial, and religious differences. In fact, studies show that working with a culturally competent professional can significantly improve outcomes.

Increasingly, that need is being addressed by individuals, not-for-profit organizations, and digital companies focused on helping racialized people find therapists who are culturally aware or share their philosophies and worldviews. Some therapists may also have the knowledge and training to combat trauma due to racism and other forms of discrimination.

Why is it so hard to find culturally competent care?

One of the reasons why racialized women in Canada and the United States struggle to access culturally competent care is a lack of diversity among mental health professionals.

There is a mismatch in North America between what the population looks like and the psychology workforce. Whereas the population is rapidly diversifying, psychologists are still overwhelmingly White. According to 2020 Census data in the United States, 57.8% of Americans identify as White, 18% as Hispanic or Latino, 12.1% as Black or African American, and 6% as Asian. Those who identify as multiple races are 10.2 percent of the population, up from 2.9% in 2010. In contrast, 84% of psychologists in the U.S. workforce were white, 6% were Hispanic, and 4% were Black, based on 2018 data.

Similarly, a quarter of adults have a disability, yet only about 5% of psychology faculty disclosed a disability in 2019.

In Canada, the Canadian Psychological Association does not collect demographic information from its members. However, a 2010 study of the composition of select Canadian psychology graduate programs showed that 91% of students entering these programs were White, 7% were Asian, 1% were Black, and 1% were Hispanic.

Clinical psychologist Monnica Williams, the Canada Research Chair in Mental Health Disparities at the University of Ottawa, said there is a lack of diversity among mental health professionals in Canada. “We don't exactly know how bad it is because no one is collecting those data. But we know it’s bad because we keep hearing people of color say they can’t find clinicians,” she says.

Given the shortage, Williams said Canada should focus on helping the mental health professionals working today gain the skills to care for people across different races, ethnicities, and cultures.

There is a lack of research on culturally competent care and guidelines to help mental health professionals deliver it. Most psychology training in North America is Eurocentric. Counseling theory, research, and practice are generally based on Western culture and developed for white, middle-class people. It has neglected the mental health concerns of other racial groups and the unique stressors they face and failed to meet their needs.

In Canada, for example, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people have disproportionately high rates of mental health problems compared to non-Indigenous Canadians. Yet, mental health services are underutilized by Indigenous people and often unsuccessful. Research suggests that this issue is partly because mental health services do not reflect Indigenous conceptions of health and healing.

Mental health initiatives like Shkaabe Makwa at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto are attempting to change that. Shkaabe Makwa was launched in 2020 to connect First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people with culturally relevant mental health services across the province. It also provides training to support workforce development and improves practice through research and knowledge exchange.

Research is critical. The need for culturally competent counseling is widely recognized. Still, there is not much data on what works — in terms of training and education for mental health professionals and effective therapies for racialized people. A recent article calling for a move toward anti-racism in Canadian psychology recommended prioritizing funding "dedicated to BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] health and wellness" and "research that considers and promotes racial diversity and equity."

How to Find Culturally Competent Care

The National Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health America have put together helpful guidelines to finding culturally competent care. Here are a few tips to keep in mind.

Think about your needs

It can be difficult to find a provider who shares specific parts of their identity with you, so consider what you really need. For example, if your mental health conditions are rooted in your gender identity, sexual orientation, or cultural identity, it may be important to find a specialized provider, rather than someone who has baseline competence.

Search for providers

There are many online directories with search functions to help you find mental health professionals who have a specialty or competency that may be relevant to your identities. In addition to online directories, reach out to acquaintances, local organizations, community centers, and health centers for referrals.

Reach out

When you call to schedule an initial meeting, ask the provider about their previous experience delivering care related to your identity or identities. Set up an initial meeting to learn more about their training and expertise, and gauge whether you will feel comfortable in the care of that provider.

Ask lots of questions — of the therapist and of yourself

Providers should expect and welcome your questions because it helps them better understand your problems and treatment needs.

At the initial meeting, ask the provider a few of these questions:

My identity is [insert your identity or identities here]. What experience do you have working with clients with that identity?

Do you have specific training or certifications that relate to working with clients with my identity?

What evidence-based treatments do you have for issues that may arise related to [insert your identity or identities here] health and wellness?

How do you define intersectionality, and how do you plan to utilize an intersectional lens in my treatment?

How can you help me navigate trauma related to the oppression I face related to my [insert your identity here] identity given that my mental health is being impacted by multiple systems of oppression?

After the meeting, ask yourself these questions:

Did my provider communicate effectively with me?

Is my provider willing to integrate my beliefs, practices, identities, and cultural background into my treatment plan?

Was I treated with respect and dignity?

Do I feel like my provider understands and relates well with me?

Resources:

We've compiled a short list of online directories and apps may help you find culturally competent mental health professionals. Note that this list is not comprehensive.

Asian Mental Health Collective (USA and Canada) - a searchable directory of Asian therapists.

Therapy for Black Girls (USA) - an online platform supporting the mental wellness of Black women and girls, including a searchable directory.

Healing in Colour (Canada) - a directory of BIPOC therapists, including a curated list of professionals with anti-oppressive values.

Black Female Therapists (USA) - an online platform created to elevate Black therapists and create a safe space for Black mental health.

InnoPsych (USA) - a directory of therapists of color.

Latinx Therapy (USA) - a national directory of Latinx therapists and speakers.

Ayana Therapy (USA) - an online platform that connects people in marginalized and intersectional communities with mental health services.

The Gay and Lesbian Medical Association's Provider Directory (USA) - a searchable directory of primary care providers, therapists, dentists, and other health professionals.

Vancouver Black Therapy & Advocacy Foundation (Vancouver, Canada) - a non-profit organization connecting Black community members to mental health resources, including therapy, advocacy, and mental health support.

The Black Healing Fund (Montreal, Canada) - a volunteer-led initiative to connect low-income Black individuals with therapists and mental health resources.

Southasiantherapists.org – an online directory of South Asian therapists worldwide.

Althea Therapy (Canada) - an app for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color that facilitates access to mental health & wellness professionals in Canada.

SavynCares – a free multilingual platform providing grounding tools to heal from trauma and manage anxiety, stress, and other emotions.

Do you have a resource to suggest?

Reach out to us at:[email protected]